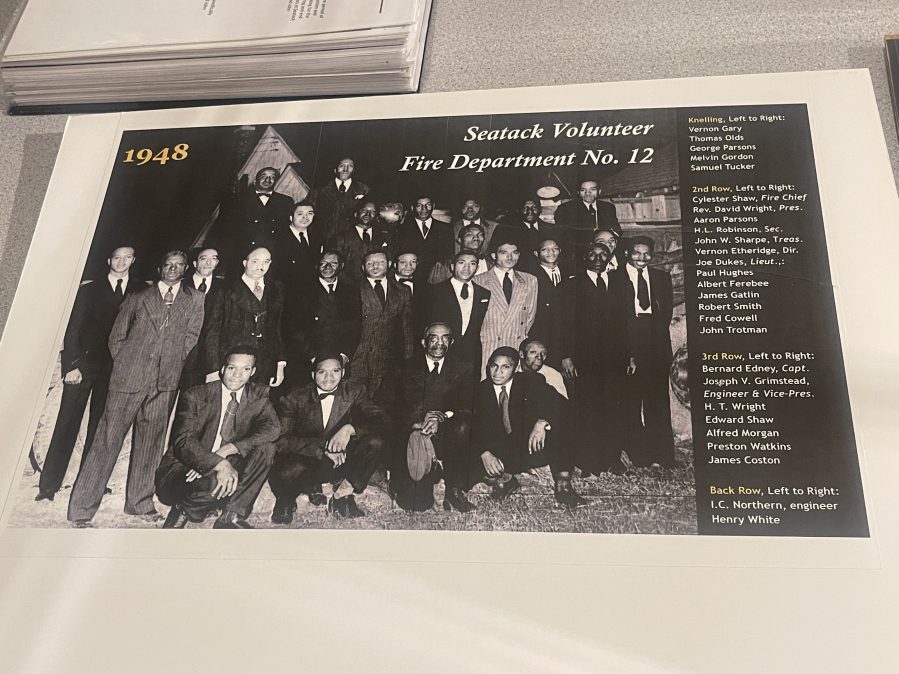

(Photo courtesy of Edna Hawkins Hendrix)

(Photo courtesy of Edna Hawkins Hendrix)

VIRGINIA BEACH, Va. (WAVY) — It’s a flame that can’t be extinguished, and still to this day, after more than 75 years, it enlightens the Seatack neighborhood of Virginia Beach.

The area housed one of the nation’s first African American-owned and operated fire stations.

“They were the trailblazers,” said historian Edna Hawkins Hendrix. “They’re the ones that made that foundation possible, with hard work, and they enjoy what they did. Because they wanted to survive. And that’s what you do when you want to survive.”

It was July 1948.

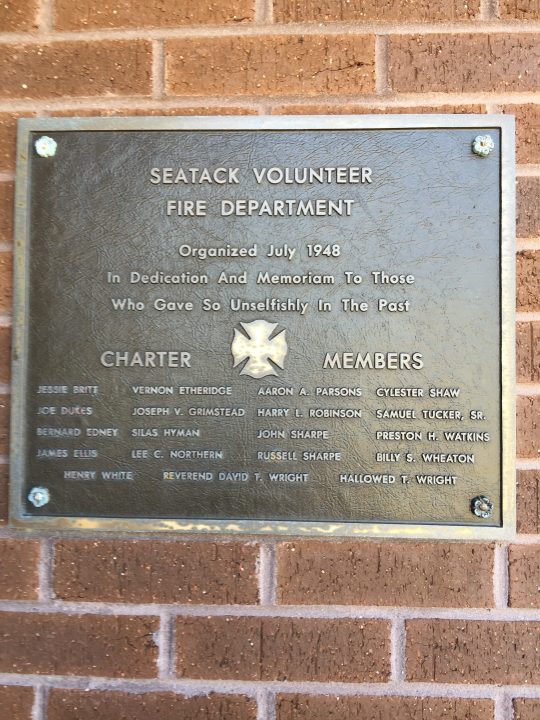

“The Reverend David Wright and 19 other men formed the Seatack Volunteer Fire Department,” said historian Jacqueline Malbon.

It was located on Birdneck Road, in the area that was called Princess Anne County. That fire station is also known as Station 12.

“This was a volunteer fire department,” Hendrix said. “These men, even when they were at work, if they heard the alarm go off, they dropped what they were doing and they came running to go put out the fire. No matter where it was. And they did go into the White neighborhoods as well.”

Joseph Grimstead founded the fire station, and the original firemen were just decades from bondage.

“Their grandparents were slaves,” Hendrix said.

She said many of the volunteers worked in fields or at the Cavalier Hotel. At the hotel, they were underpaid compared to their White counterparts, but they were motivated to fight fires for free because of the expense the county charged to do it.

“They had to pay $50 to Virginia Beach, well, then Princess Anne County to put out fires for them,” Hendrix said. “That was a standard fee that the Princess Anne County charged for their fire department to come out and put out any fire, both Black and White would charge that.”

Research shows $50 in the late 1940s is around $700 now.

“Back in those times, it was very hard for African Americans to come up with that $50,” Hendrix said. “So most of the time they probably didn’t even call them to come in because they didn’t have the money.”

That struggle motivated Seatack’s Black community to find a solution.

“They decided, well, we can do our own because we’ve already had the training as a civil defense,” Hendrix said.

During World War II, the government provided funding to Civil Defense Units in the Tidewater area. The Oceana Civil Defense in Seatack used the money to purchase firefighting tools.

However, due to Jim Crow laws, they had to be careful.

“Everything that they did, they did it in secret because they didn’t want them to know what they were doing,” Hendrix said. Because if they did, they would try to stop them.

The Oceana Civil Defense transformed the their civil defense building into the fire station. The men’s wives played a huge role in the process.

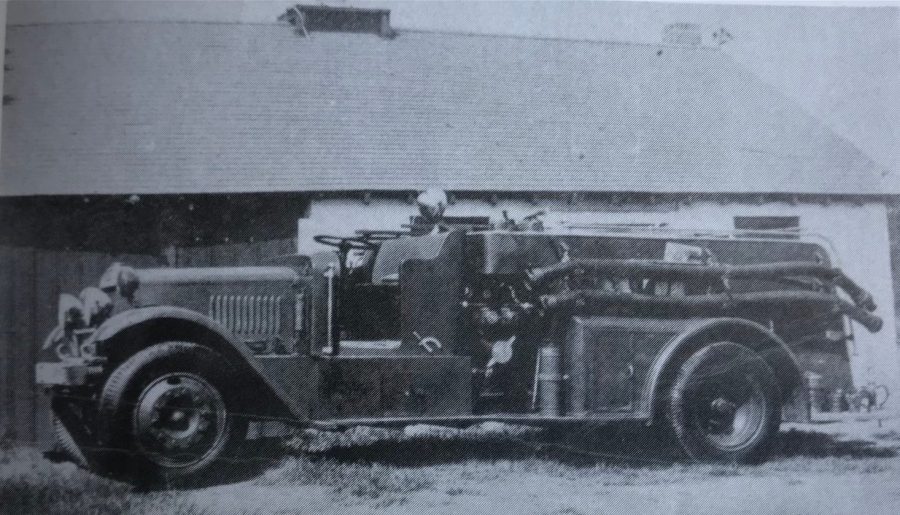

“The women of Seatack were the ones that raised the money to purchase all of their equipment, which was Big Bertha,” Hendrix said.

She was red in color and the first piece of equipment bought. Big Bertha looked like a cross between a tank and a boxcar.

The wives, known as the auxiliary, hosted bake sales and held fundraisers to raise money for the fire department. They also went to the fire scenes to ensure their husbands had water.

(Photo courtesy of Edna Hawkins Hendrix)

(Photo courtesy of Edna Hawkins Hendrix)

“Even the wives, the auxiliary had to be available to assist the families that had the fires,” Malbon said.

Hendrix said as volunteers, Station 12 put more effort into fighting fires than the county fire department.

“Mrs. Shaw talked about that a house was completely burned down by the time the White fire

station got there,” she said, “and the only thing they did was pull the hose out and just spray

a little water on the smut that was left. And that’s what really turned them off — that it was time that they do something about that because they had too many of those going on in their neighborhoods.”

Hendrix said patrons at the Cavalier recognized the men and would tip them more than the White waiters.

“They decided to get rid of the Black waiters and hire White waiters so that they could get that tip money,” she said. “But they had to bring the Blacks. And that’s because the Whites couldn’t do what the Blacks would.”

She said it was a community effort to keep the fire station running. Even Black churches helped the men with many odds stacked against them.

“Volunteer[s], with no help from the city … these men pulled together and kept this fire station going,” Hendrix said. “And the building also became a voting center for African-Americans.”

Around the late 1960s, the fire department became integrated because they needed more men to fight fires.

In 1976, the first paid firefighter joined.

In the 1980s, Seatack got a new fire station, and Grimstead signed the deed to the historic one over to the city so it could become a recreation center.

That recreation center is now named after Grimstead — the Joseph V. Grimstead, Sr. Seatack Recreation Center.

The recreation center has a plaque of deed and names of Station 12 firemen who’ve died.

“They had many trials to face, and sometimes the world was not kind, but they they persevered,” Malbon said. “They paved the way for the second generation to follow in their footsteps.”