NORFOLK, Va. (WAVY) — Jessica Person was pregnant with twins in 2014 when a normal routine obstetrics appointment went awry.

Her blood pressure kept going up and her tests didn’t come back normal despite not having any symptoms. Instead, the soon-to-be mother got some concerning news.

“So they said, ‘We’re going to refer you to a nephrologist, or kidney doctor,'” Jessica said. “And, she did more tests. She looked at my levels and said, ‘You have chronic kidney disease.”

On New Year’s Eve she had her twins, and two days later, Jessica had a biopsy. The doctors confirmed Jessica had lupus nephritis, an autoimmune disease attacking the kidneys.

For years, the kidney disease was monitored and managed. However, from 2020-2022, her kidney health slowly started to deteriorate, and it got much worse.

In December 2022, Jessica began dialysis.

“I think the day she told me, ‘OK, we reached the point where you need to get dialysis and think about a transplant’, I was like, ‘OK, this is real,'” Jessica said.

Dr. Duncan Yoder is the Surgical Director for Sentara’s Transplant Center. In 1972, Sentara Norfolk General Hospital began kidney transplants. Since then, they have done over 2,000 successful transplants.

Digital Host Sarah Goode spoke to Yoder in a Digital Desk LIVE to debunk misinformation, understand kidney transplants and discuss being a donor. Watch the video in the player, below.

Yoder said patients on dialysis typically go to a dialysis center three times a week for 3-4 hours at a time.

“It’s certainly not a lifestyle anyone would choose,” Yoder said.

The longer someone is on dialysis, the more of a toll it takes on the body, Yoder added.

“If you are somebody that wants to work, or travel, or just spend time with family, doing different hobbies you enjoy, it can be real challenging when you’re committed to dialysis,” Yoder said. “So, transplant really does give you a new lease on life to enjoy those things, do things, to be able to do the things you want to do and not have to worry about dialyzing each week.”

Jessica did dialysis at home. Boxes took up her living room. She managed dialysis with her life, work and raising her kids.

Once patients are on dialysis and are referred for a transplant, it could take three to five years for a deceased donor transplant, if they don’t have a living donor able to donate.

Finding donors has always been a challenge for the Hampton Roads area.

“The community here with kidney failure is predominantly African-American and unfortunately, diabetes and hypertension — it runs in the community, and is more prevalent in the African-American group,” Yoder said.

The issue is worsened by the facts that they also have a harder time finding acceptable donors to donate, and some patients cannot have transplants, Yoder said.

Several factors could impact a recipient’s ability to match, including antibody levels and previous transplants. Those who meet the recipient criteria have better outcomes if transplanted.

“Transplant is the best option for them if they’re on dialysis or looking like they are progressing to dialysis,” Yoder said. “The outcomes are just so much better, whether you get a couple years from your transplant or you get fifty years from your transplant. Any time off of dialysis is better for them.”

Jessica began working to find a match.

After having surgery for a peritoneal dialysis (PD) catheter, the medical team began sending her information on transplants. She had to take different classes to learn more. They also created a card and link for her to post on social media and share with friends and family to help her find a match.

“Typically, family members tend to be better matches,” Yoder said. Luckily for Jessica, her family supported her right away and said they would get tested. Her sister tested first, but with some donor antibodies, it would have been a higher risk for rejection.

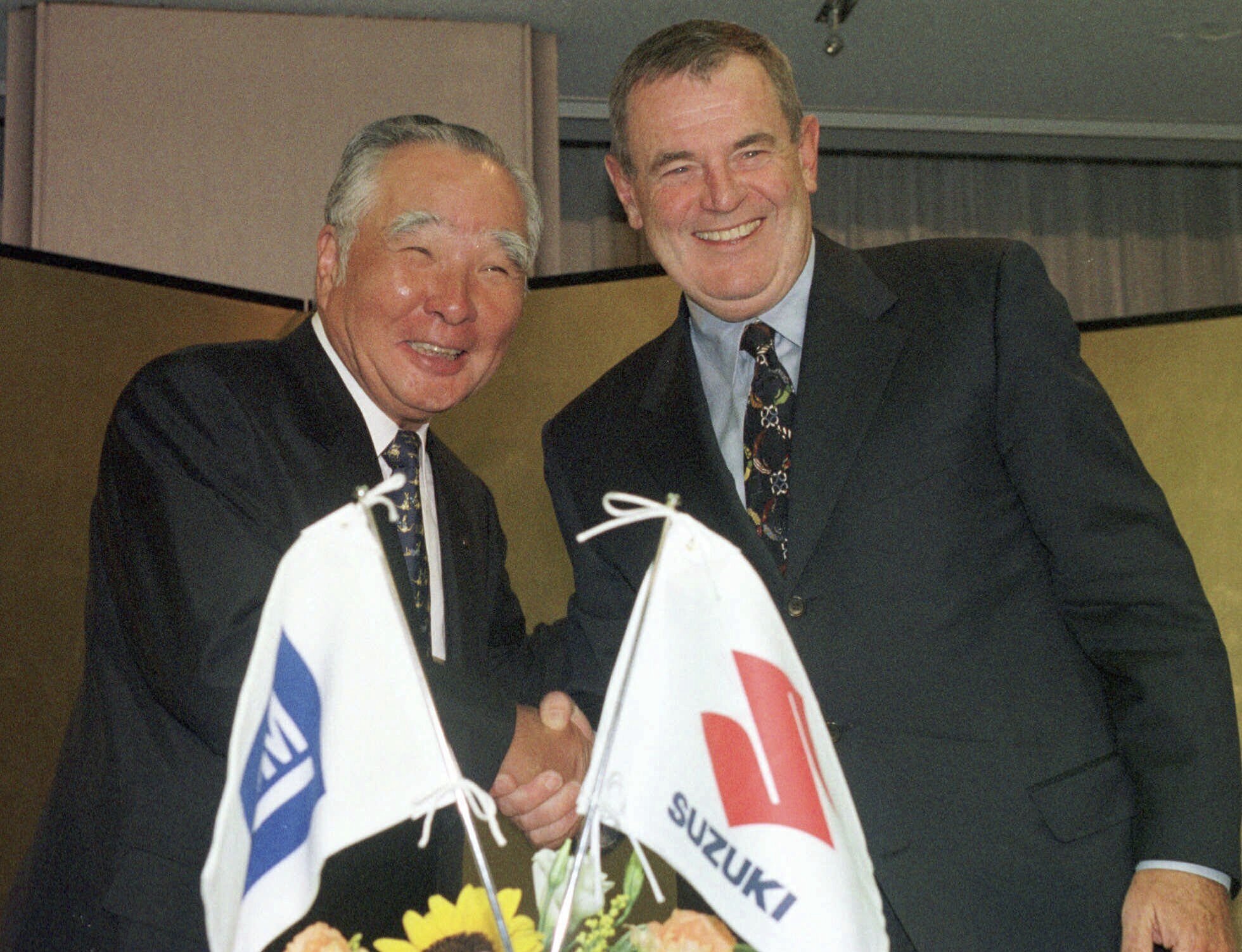

“So they were like, ‘If we have to use her we will,'” Jessica said. “Then, my Dad got tested and he’s a match, that’s great”.

David said his immediate reaction was concern and fear. But, he was ready to help.

“My faith led me there,” David said. “So, once she asked the family to be tested, I actually had planned to be the first one, but my second daughter beat me to the punch. But, I told them, if I was a match, I was going to do it.”

There are criteria donors have to hit. David had regular blood pressure checks to monitor.

“The last thing you want to do is remove a kidney from someone who has risk factors for early kidney disease or dialysis,” Yoder said.

Each donor goes through similar evaluation process to the recipients to make sure they are safe for donation and make sure they do not have risks for early kidney disease.

“Once we got through that process we were ready to go,” David said.

Donors have excellent outcomes, they have the same life expectancy and same rates of chronic kidney disease as the average population.

In December 2023, about a year after starting dialysis, Jessica received a new kidney from her Dad.

After a transplant, Yoder said the most important thing is to make sure patients take the immune suppression on a regular basis, which are medications to prevent rejection.

For the first month, Jessica had weekly checkups. Those visits decreased to twice a month and now, monthly appointments.

How long can kidneys last? It depends.

In 2022, at Sentara’s 50th Anniversary of the transplant program, they celebrated the successful, original transplant for identical twins. 50 years later, the kidney is still working for the recipient.

“Patients can have outstanding outcomes like that,” Yoder said. “The average lifespan of a kidney isn’t quite that long. But, if you have transplant and it starts to peter out or fail, you can be rereferred for another transplant.”

There are many patients that have two or even three transplants throughout their life, said Yoder.

As of March 2024, there are over 100,000 people on the national transplant waiting list, according to the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network. Patients on the waiting list for kidneys surpass the amount of patients for liver, pancreas, heart and more.

Currently, over 89,000 patients are on the national waiting list for a kidney.

Programs are helping fill the void, but it is not closing the gap yet.

“The gap between the number of patients that need a transplant and the number of donors is still widening and so it helps to have programs these programs like NKR (National Kidney Registry) and paired exchange programs, but certainly is not making up that difference yet,” Yoder said.

So, why is there a lack of donors?

“It’s probably a lot of misinformation and that’s why it’s important to displace any myths that are out there and provide patients with awareness about the process,” Yoder said.

In our region, most of the causes for kidney transplant is high blood pressure or diabetes leading to kidney disease then failure.

Yoder’s team works with patients at the Children’s Hospital of the King’s Daughters, or CHKD, and Sentara Norfolk General Hospital. It’s a smaller population at CHKD, where kids can develop kidney failure due to congenital issues.

At the hospital, it mostly impacts adults later in life. Typically, the patients also present with other chronic diseases, making it more difficult to treat.

“Sometimes the scary thing is a lot of these patients will just kind of show up in the ER with symptoms of end stage kidney disease,” Yoder said. “And, they really had no idea that their kidneys had been failing for a long time.”

Symptoms sometimes do not present until later on. He recommended and encourages people to get regular checkups.

“When we see them, a lot of our patients in particular, are in end stage kidney failure, end up requiring dialysis at time of their diagnosis,” Yoder said. “And, so that can be sort of a scary process for them. There’s obviously a lot of information and education that comes along with that. And, sometimes it can be almost overwhelming.”

For dad and daughter, the recovery process was manageable. With support from family, friends, church and work they were able to rest and move forward.

“I don’t know how anyone, even being a donor, without having support of family and friends, it would be traumatic,” David said. “But, it was very helpful.”

Now, Jessica’s health is back.

“I eat more,” Jessica said. “I used to really not eat at all for a very long time. But, I do feel like I have more energy sometimes. I’m good.”

Her kids hardly notice a change in their mom.

“Other than the 50 billion boxes that I had in my room for my dialysis stuff, I don’t really think they notice,” Jessica said.

Jessica said it was never a concern whether or not her family would support her or donate, if they were a match.

“I actually kind of knew they would,” Jessica said. “They’re all very, we’re all very invested in each other. So, it wasn’t a question if anybody would or wouldn’t.”

Prior Jessica’s health and the kidney transplant, David was not familiar with being a donor. Now, he realizes the significance and importance.

“To be honest, I didn’t think about it before,” David said. “Now, because I see the personal investment that my family did, from me donating my kidney to my daughter, I think it’s very important we should look beyond ourselves when we can help family member or friend, even in life or transition.”

David said there is a level of distrust in the African-American community with the medical field. Now, he encourages people to learn more about being a donor. Their experience has already spurred conversations within their extended family, as family members have also been in need of kidney transplants.

Ultimately, David credits his faith through everything. It led him to being a donor for his daughter.

Now, at 33, Jessica can focus on her life and four kids with a healthy kidney.

“I think it’s really important,” Jessica said. “I mean, especially with a kidney. You only need one is what they say. But, you definitely could, or not could, you definitely would save someone’s life. Help them have a better life. A better quality of life.”

April is Donate Life Month. Sentara celebrated with a flag raising to raise awareness.

If you are interested in being a donor, find out more about the Living Donor Kidney Transplant at Sentara.

Watch the LIVE Digital Desk conversation on this page to find out more about kidney transplants and being a donor.