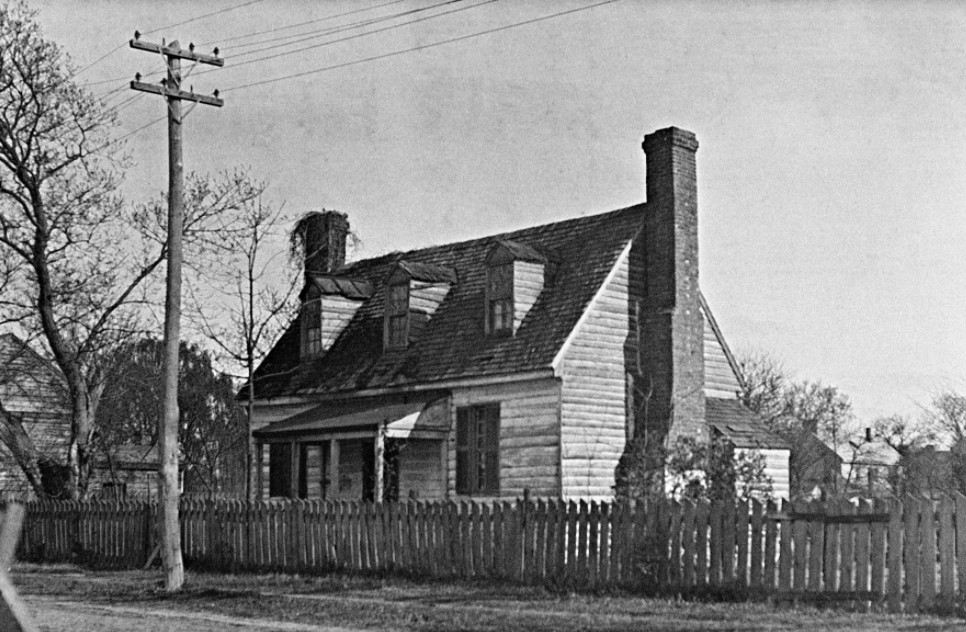

WILLIAMSBURG, Va. (WAVY)- The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation is partnering with the College of William & Mary to relocate a building that once housed a school for free and enslaved black children.

The Bray School, which was suggested to be established by Benjamin Franklin, operated between 1760 to 1774 and educated around 400 students, according to Ron Hurst who is vice president for museums, preservation, and historic resources for the foundation. Currently, it’s owned by the university.

“Colonial Williamsburg, in partnership with our neighbor William & Mary, are looking to restore this building to its 18th-century appearance and relocate it to the historic area and talk about the education of Black children in the 18th century, which many people didn’t know of until it came to life,” Hurst said.

Dendrochronology analysis dated the foundation of the building from the late 1750s. After receiving the results last year, Hurst says Colonial Williamsburg started working with the school to start the process for relocation.

But, the journey actually begins almost 20 years ago when Terry Meyers. Meyers is a chancellor professor, emeritus of English, and worked at William & Mary for nearly 40 years. He started digging into research about the building in the early 2000s.

“I first heard there was an 18th-century cottage moved from its original site just 100 yards in 2003/2004 from reading a memoir,” Meyers said.

Even though he knew where the location was, Meyers says he could not spot it at the time, but decided to do more research. Eventually, he found what he was looking for after coming across a file in the special collections section at the John D. Rockefeller Jr. Library.

“I came back here and began to look at the building with new eyes. If you move the roofline back and subtract the additions, you have an 18th-century cottage,” he said.

Meyers says he’s always been interested in things overlooked or suppressed in history and believes that’s what’s drawn him to the story of the cottage and school.

“I began to read about the Bray School and discovered a list of students that had been educated here including two named Adam and Fannie, who were educated and owned by the college. I know in a large broadway, William & Mary was an old southern school and we must be implicated in slavery in some way,” he said.

Meyers says he published his first work on his findings in the Virginia Gazette in 2004 and believes his research helped lead to the Lemon Project, which was established by the university as a journey toward reconciliation with a complicated racial past.

It’s a story that Colonial Williamsburg has also been working to tell more of over the last 40 years.

“Our aspect here is to always tell everything, the entire story. When half of the population is Black, whether free or slave and it’s not half of the story, you’ve been missing something. We’re very excited about this,” said Hurst.

During the 18th century, 52 percent of Colonial Williamsburg’s population was Black. Projects like the relocation of the school and the First Baptist archaeological dig are just a few ways the foundation has worked recently to help tell a more complete story.

“This is a great opportunity to tell the lives of both free and enslaved Black children and we think it’s going to be surprising for a lot of people who come and visit,” he said.

Hurst says those like tavern keepers, printers, and gentry paid for the children of enslaved staff to be educated as well as families of freed Blacks.

The school taught Pro-slavery ideals through Christianity such as its tenets on humility and servitude but Meyers says that education still would’ve impacted the students in a bigger way.

“Education is something that tends to make people independent,” he said.

Meyers, who leads tours of William & Mary’s racial history from time to time, says he was excited to finally hear that he could officially say the building housed the school and that it’s important to tell people of its complicated history.

“It’s vitally important,” he said. “I’m interested in things that have been overlooked, forgotten, and suppressed and that’s certainly been true when it comes to the way we’ve treated African Americans in slavery or post-Reconstruction and Jim Crow segregation. We’ve overlooked that and forgotten it. It’s a complicated history and I’ve forgotten that,” he said.

The building, which was moved to its current spot on Prince George Street in 1930, will be analyzed by the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation for a year. It will then be relocated in 2022 and will be restored to its original structure before opening for the public in the historic area in 2024.

Hurst says it will open in time for the 250th anniversary of the school’s closing.

Meyers, who’s put many years into researching the school, hopes his legacy will include his contributions to discovering and restoring it.

“It pleases me greatly,” he said.