HAMPTON, Va. (WAVY) — After admitting that a seasoned investigator denied a man’s right to an attorney during questioning, Hampton Police Chief Mark Talbot said his department has policies in place that should have allowed them to “do better.”

“We have our own obligation to maintain the highest standards of conduct to make sure that we’re not skirting any lines that appear to be inappropriate or questionable,” Talbot said in a press conference on Monday.

Talbot’s admission came more than a week after he publicly denied that Cory Bigsby ever requested an attorney during three days of police questioning related to the disappearance of his son, Codi. The father first reported his 4-year-old son missing on Jan. 31 and quickly became the police department’s main person of interest. He remained at police headquarters until Feb. 3, when he was charged with seven counts of felony child neglect. Those charges are not directly related to Codi’s disappearance.

During the first few days of the investigation, Talbot repeatedly told the public that Bigsby was at police headquarters voluntarily; however, questions about his voluntary status were raised hours before the felony charges became public when attorney Jeffrey Ambrose, who was hired by Bigsby’s family, tried to speak with the father but was denied access to him by Hampton police officers.

“Mr. Bigsby is a 43-year-old man who’s had a full career in the Army,” Talbot said during a press conference on Feb. 4. “He seems to be quite intelligent. He seems to be quite capable, and part of that capability seems to be understanding his rights. At no time did he request to see an attorney. Had he made such a request, we would have honored that request.”

On Monday, Talbot admitted that his previous statement regarding Bigsby’s request for an attorney was wrong, citing “bad information” he’d received from investigators. Talbot said the lead detective in the case “mishandled” two requests for an attorney that Bigsby made during the early morning hours of Feb. 1. Those requests for counsel came during a “heated exchange” between Bigsby and the lead investigator about the results of a polygraph the father took around 10 p.m. on Jan. 31, Talbot said.

“My assessment of his statement in that moment, and a statement he made several minutes later that was similar, expressing a desire for legal counsel, my assessment is that his desires should have been honored,” Talbot said. “They weren’t.”

The lead detective was pulled from the case and put on paid leave, and a new investigator has been appointed, Talbot said.

Talbot became aware of problems with the interrogation late Friday afternoon and immediately launched a full audit of nearly 100 hours of recorded interactions between police and Bigsby. That audit showed investigators read Bigsby the Miranda Warning at least twice — when he was initially questioned and before a federal agency administered the polygraph test. He waived those rights until he requested an attorney for the first time around 4:13 a.m. on Feb. 1, Talbot said.

The Miranda Warning was established by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1966 to protect Americans’ constitutional rights to remain silent and have an attorney present during police questioning. Police must make a person aware of their rights ahead of an interrogation, according to the Cornell Law School’s Legal Information Institute.

Even if a person waives their Miranda Warning rights initially, they can invoke the ability to remain silent or ask for an attorney at any point during police questioning. Police should stop questioning a person after they’ve requested an attorney, according to the American Civil Liberties Union.

“You have the right to remain silent. Anything you say can and will be used against you in a court of law. You have the right to an attorney.”

Miranda Warning

Some high-profile and precedent-setting national cases involved Miranda rights and police interrogations. The right to an attorney is one of the key aspects of the Miranda Warning, and cases can pivot on whether law enforcement gives a clear explanation of that right.

A 1998 double murder conviction in Los Angeles was reduced from first-degree murder to second-degree because of an improper interrogation. Reuben Lujan ambushed his estranged wife and their sheriff’s deputy neighbor — beating them both to death with a chunk of concrete. A federal appeals court ruled that Lujan was not properly advised of his right to an attorney.

The U.S. Supreme Court reversed a 1997 Missouri murder and arson conviction. Patrice Seibert set her mobile home ablaze to hide the malnutrition death of her son with cerebral palsy, but in the process killed a teenager who was in the home. The high court’s ruling said the officer’s pattern of question-first before reading Miranda rights was illegal, and violated Seibert’s rights under the Fifth and 14th amendments.

Talbot does not believe the former lead investigator’s mishandling of the Bigsby interrogation will impact the seven felony child neglect charges the man is facing, although he said Hampton Commonwealth’s Attorney Anton Bell will make the final call. Talbot said that all of the information police gathered to secure those charges was discovered before Bigsby asked for an attorney.

Talbot said the former lead detective is a seasoned investigator who’s been on the force for 11 years. Talbot said that the investigator’s professional experience and HPD policies on interrogations “broke down” in the process of the Bigsby interview.

“We need to spend some time figuring out how it broke down, why it broke down, and putting things into place so it doesn’t happen again,” Talbot continued.

10 On Your Side investigators requested copies of the policies Talbot referred to in the Feb. 14 press conference where he discussed the mishandling of the case. The HPD released three policies that address constitutional rights and police authority, recording custodial interviews and interrogations, and interview and interrogation rooms.

10 On Your Side investigators asked the HPD to tell us specifically which pieces of the policies weren’t properly adhered to in the Bigsby case, but we hadn’t received clarification prior to publication of this report.

Our investigative team reviewed the policies and broke down their importance.

Constitutional requirements and police authority

This policy was developed to ensure officers comply with constitutional requirements during investigations, understand the scope of their authority, and disclose exculpatory information under the Brady Rule. It also addresses police limitations involving search and seizures and eyewitness identification.

A section of the policy is dedicated to the Fifth Amendment right people have against self-incrimination and when a Miranda Warning must be given. It says a Miranda Warning must be administered when a person is in custody and is subject to an interrogation. After issuing a Miranda Warning, officers must ask a suspect if they understand their rights and get an affirmative response before proceeding with the interrogation.

Recording custodial interviews and interrogations

This policy was established to provide direction for recording interviews and interrogations during criminal investigations. It also offers guidance to ensure a suspect’s Constitutional rights are not violated. If followed correctly, this policy protects interviewing officers from being accused of coercion, misconduct, and suspect statement distortion.

The HPD requires officers to record all interviews and interrogations with people suspected of felony crimes whenever it is possible. The policy states that every recorded interview should begin with a Miranda Warning. On rare occasions when a suspect will not cooperate because they know their statements are being recorded, officers may proceed with “traditional interview techniques” like taking handwritten notes.

Interview/interrogation rooms

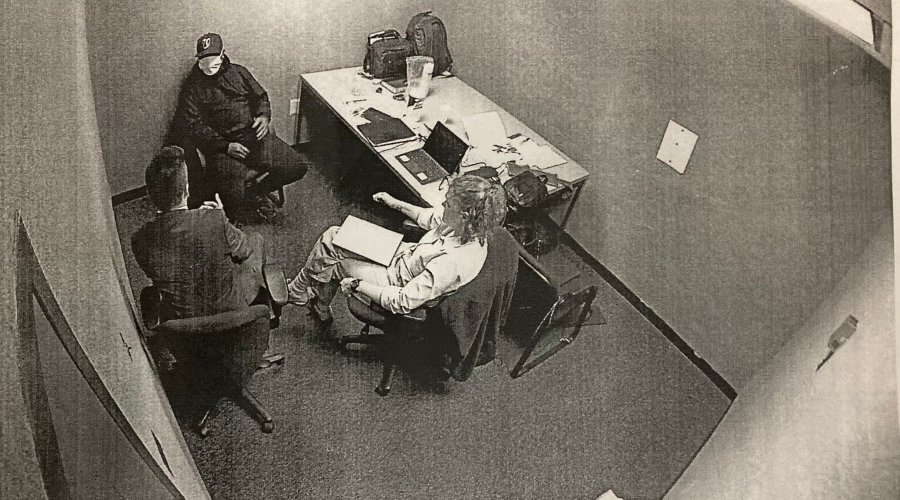

This policy was developed to set guidelines for where interrogations and interviews can be conducted during a criminal investigation. The HPD uses four small rooms to interview victims, witnesses, suspects, and defendants.

The policy defines different sets of expectations depending on the type of person being questioned.

Custodial interviews

- Suspects must be searched for weapons

- Suspects must be handcuffed before they enter an interview room, although officers may remove the handcuffs at their discretion

- HPD staff must keep a set of eyes on a suspect if they are left alone in an interview room through a peep hole, an open door, or a video monitoring system

- Officers must maintain the human needs of a suspect, including restrooms, water, and breaks

- Officers must place their weapons in secured lockboxes before entering an interview room

- Typically no more than two officers will be involved in an interview at one time

- Interviewing officers should have another officer in the area for safety or access to a police radio or telephone

- Video and audio recordings of interviews should follow HPD policy

Non-custodial interviews

- Officers may frisk a person for weapons if they believe it is necessary and should ask the suspect or witness to consent to the search

- Witnesses shouldn’t be left alone in an interview room for extended periods of time, and officers should make visual contact of a witness at least once every 10 minutes